The rise of Riso 🎨 🖨 🖼

Stencil us in.

So many of printmaking’s most celebrated techniques are treasured, traditional skills that have been around for a long time. Screen printing dates back over a thousand years to China’s Song dynasty, and woodcuts are even older. Engraving and etching first made an appearance in the 15th and 16th centuries; lithography was invented in 1796. Linocuts gained popularity at the beginning of the 20th century, and there was a boom in potato printing during World War II thanks to teacher and artist Peggy Angus.

One of our favourite methods, however, is much more modern than all that, and despite a handmade feel, it uses a 1980s office printer and photocopier called a Risograph to produce its prints. In recent years especially, this bulky grey machine has been commandeered by artists and designers who adore its gloriously vibrant results.

In 1958, the Riso Kagaku Corporation – Riso (pronounced ree-so) is the Japanese word for “ideal,” and Kagaku means “science” – found inspiration in earlier mimeograph machines to make a nifty printing device named the Riso-Graph. Then, in 1980, having become even more sophisticated and much less hyphenated, the first Risograph-branded duplicator was launched.

Marketed as “the world’s first stencil printer with fully automatic inking,” it was popular in offices and schools in its native Japan for its low running costs and high-speed printing. A few years later, the Risograph made its way to other parts of the world and, eventually, into art schools and print studios. Riso prints use soy and rice inks, and the finished effect resembles a sort of digital screen print, with a grainy texture and lovely gradients that are, frankly, wasted on Clive from Accounts and his colour-coded spreadsheets.

The technique sounds – and often looks – deceptively simple, but of course, it takes a high-tech contraption to create prints that look charmingly lo-fi. Inside the printer, each colour gets its own stencil, generated by the Risograph once the original artwork (separated into layers and converted to black and white) is either scanned in or digitally sent to it. Those stencils are then wrapped around drums of different coloured inks, and with a touch of a button, the colours are printed one on top of each other until the print is finished.

The great draw of the Risograph printer, aside from the fact it can churn out copy after copy cheaply and reliably (each machine can print around 5,000,000 pages during its lifetime), is the bold, bright colours it produces. Unlike bog-standard inkjet printers, artists can move beyond the standard CMYK colours of cyan, magenta, yellow and black, and add fluorescents or metallics, too. By overprinting, new shades can be made, and there’s lots of enjoyment to be had in experimenting – imperfections and the high chance of misregistration (when each layer is ever so slightly misaligned) just adds to the intrigue of what the final print will look like.

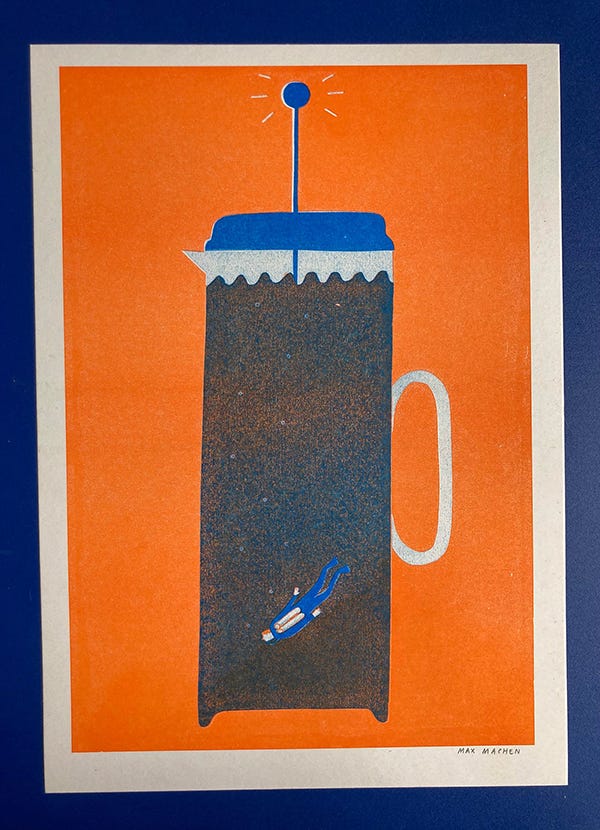

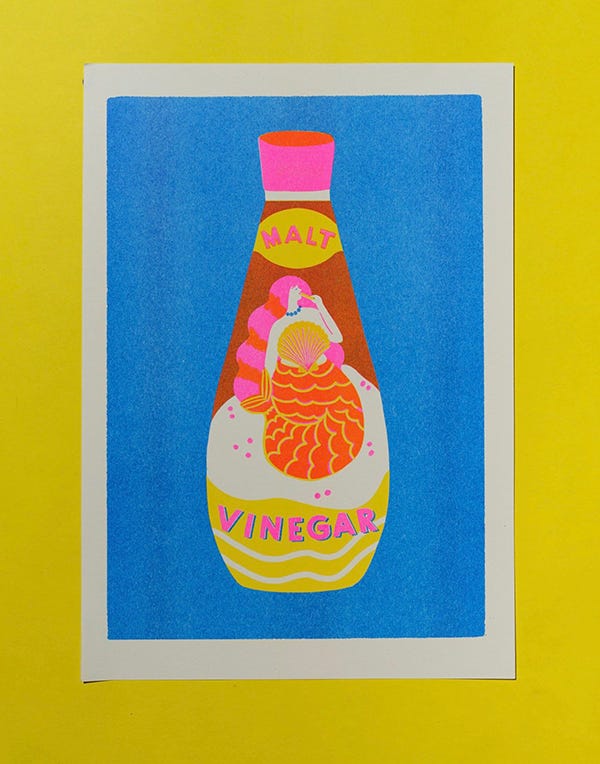

There’s been a resurgence in Riso over the past few years, with a new wave of printmakers relying on a trusty Risograph to bring their illustrations to life. We’ve featured just a handful of our favourites in this newsletter – Becky Mann, whose Orangina print is waiting to be framed so it can adorn Laura’s living room wall; Max Machen and his extremely joyful artworks; Melissa Donne’s beautiful modern botanicals; Vicki Johnson (aka Printer Johnson) with her vivid, detailed prints that prove what an awful lot four colours can achieve; and Naomi Wilkinson’s irresistible vinegar bottle, which is inevitably going to become a go-to gift for all the chip lovers in our lives (everyone).

Riso print collectives like Riso Soup and Riso Sur Mer are doing really interesting things with Risographs – publishing zines, making limited editions, and introducing the general public to the wonders of this accessible technique. And if you fancy having a go yourself, lots of print studios offer courses and taster sessions: check out Dundee Contemporary Arts, RISOTTO Studio in Glasgow, Portsmouth’s foursandeights, and East London Printmakers, who can all teach you the ways of this fascinating process that blends old and new, mechanised and manual, and – above all – fun and frolics.

This week, Sian’s been admiring Greece’s shades of blue, while Laura’s been thinking about Tunnock’s wafer blondies. Like what we do? Buy us a cuppa.