Quick as a Fox 🦊🍂🌃

Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.

In this week’s issue, Sian explores the most curious of creatures: the urban fox.

It is a clear, crisp winter evening. You’re on the way home with half an eye on the road as you cross diagonally, hurrying to get out of the cold. Then you see it. The flash of amber, the spruce of a tail.

More than 150,000 of the UK’s 350,000 foxes live in cities, more than any other country. Our ever-expanding cities have forced them into urban spaces despite the risks to their safety.

Our relationship with foxes has never been an easy one. We have always been distrustful of them. Their cunning was cemented by Aesop – foxes are tricksters, they’ve got guile. Their reputation for sneakiness has been personified in several of Shakespeare’s plays. It’s not all undue fabrication – there was a time when the chicken dinner antics of a fox could destroy livelihoods.

The myth has been perpetuated further in more recent culture. Beatrix Potter villainised the fox in Jemima Puddleduck. Roald Dahl never shied away from the cunning nature of his main character in Fantastic Mr Fox, even though it was painted as something of a positive – Fox’s trickery wins out in the end. Disney’s position is clear: foxes are disloyal and they steal what isn’t theirs. They were given something of a reprieve in beloved children’s books and subsequent BBC series The Animals Of Farthing Wood. While author Colin Dann couldn’t overhaul their much-maligned reputation, he did address the issue of humans encroaching on countryside spaces, forcing the foxes to make their homes inside cities.

And here they are, in their thousands. There are 10,000 foxes living in London alone. Some people understandably view urban foxes as nothing more than pests. They have tremendously noisy mating habits and they tear open our rubbish bags for their midnight feasts – household waste makes up around 50% of a city fox’s diet.

Yet for many people – myself included – the sighting of an urban fox is an unexpected gift. I once lost most of a morning watching a family of cubs scamping about a southeast London garden. Now, north of the river, there’s a little fox that likes to curl up in a patio corner by our flat – I can just see the white of his pointy nose from my living room. He likes to catch the morning sunlight as it floods over the building and doesn’t even stir when our neighbours walk by. The sheltered sunny spot is clearly worth the risk. Urban foxes are by no means tame but they are willing to get closer to us than we anticipate.

That closeness has become more common in recent years. Foxes began moving into cities during the Second World War, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that they became truly settled in. Now they’re a part of city life but not quite a daily occurrence. Sightings are neither common or rare. We regard them differently to other city animals such as rats or pigeons. Perhaps the notoriety that we bestowed upon them is partly the reason. A fox crossing your path feels like a spell has been cast. That it is in the everyday makes it special. A connection to nature is a rare occurrence in a city so when it does happen, it dumbfounds us.

Mobile phone cameras are ill-equipped to capture magic. An orange blur with glinty eyes is the best you can hope for. The sighting becomes a silent, unshareable moment.

Yet it is impossible for a fox to pass without exclaiming. It is too extraordinary. Sometimes you glimpse just a dash of a tail between a row of parked cars, sometimes they continue their trot down the street. Once in a while they look right at you and it is arresting. If I was a believer in such things – and perhaps today I am – I’d be inclined to think it was a sign of something.

It is a clear, crisp winter evening. A fox takes a diagonal path across an empty road and then it sees you. It stops and stares, before slinking off into the darkness. You continue your journey home, entirely unchanged by such a remarkable event.

Tails of the city

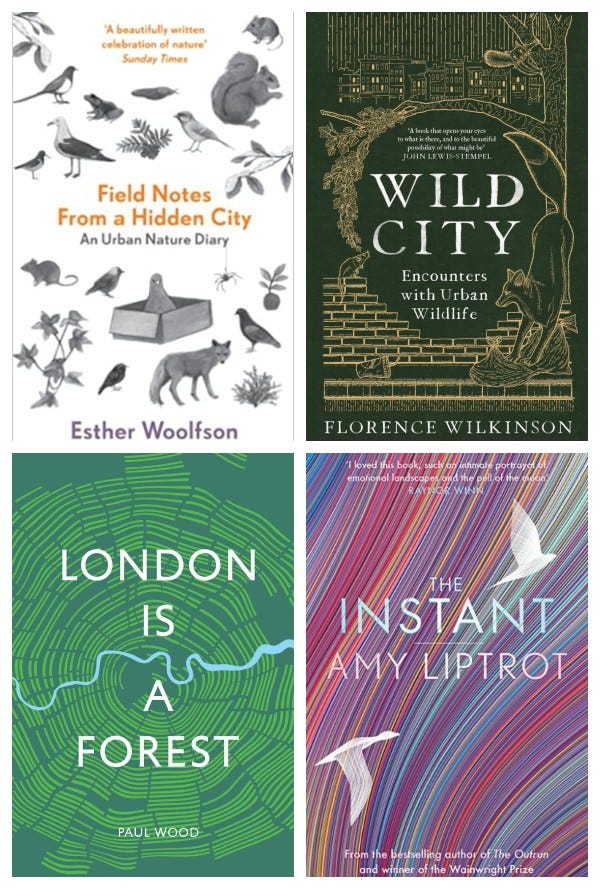

Our urban environments are home to a whole host of wonderful animals as well as the handsome fox, if you know where to look and what you’re looking for. These brilliant books will inspire you to see those familiar streets in a new light.

In Field Notes from a Hidden City, Esther Woolfson documents the goings-on of Aberdeen’s wildest residents, from squirrels and herring gulls to rats and worms, over the course of a year. She paints a beautiful portrait of the city and its abundant nature, and delves deeper into the strange – and sometimes strained – relationships we have with furry and feathered locals.

Florence Wilkinson urges us to get to know our neighbours in Wild City. Not Sheila at number 6, mind (steer clear, she’s a gossipmonger), but the wildlife that roams around our towns and cities and has adapted to survive, and often thrive, among the people and the buildings. Expect foxes, bats, peregrine falcons, and, um, the London Underground’s mosquito subspecies.

Her first memoir of recovery played out against the wild and wonderful backdrop of Orkney, with a huge supporting cast of creatures. In The Instant, Amy Liptrot’s second book, the writer heads to Berlin, where her hunt for love and the subsequent pain of its loss are punctuated by bouts of birdwatching, and a search for the city’s elusive raccoons.

There are around 9 million people and 8.5 million trees living together in London’s 600 square miles, which technically makes the capital a forest. London is a Forest by (in a spectacular display of nominative determinism) Paul Wood takes us on several different trails to explore these urban trees and their inhabitants.

We’ve been out-foxed: a sly sip | on the prowl | ruff and ready | fantastically adaptable Mr Fox | knit your own | he’s not impressed by your cooking skills.

This week, Laura’s been practising her Gaelic and Sian has been to her first basketball game. Like what we do? Buy us a cuppa or read our book.